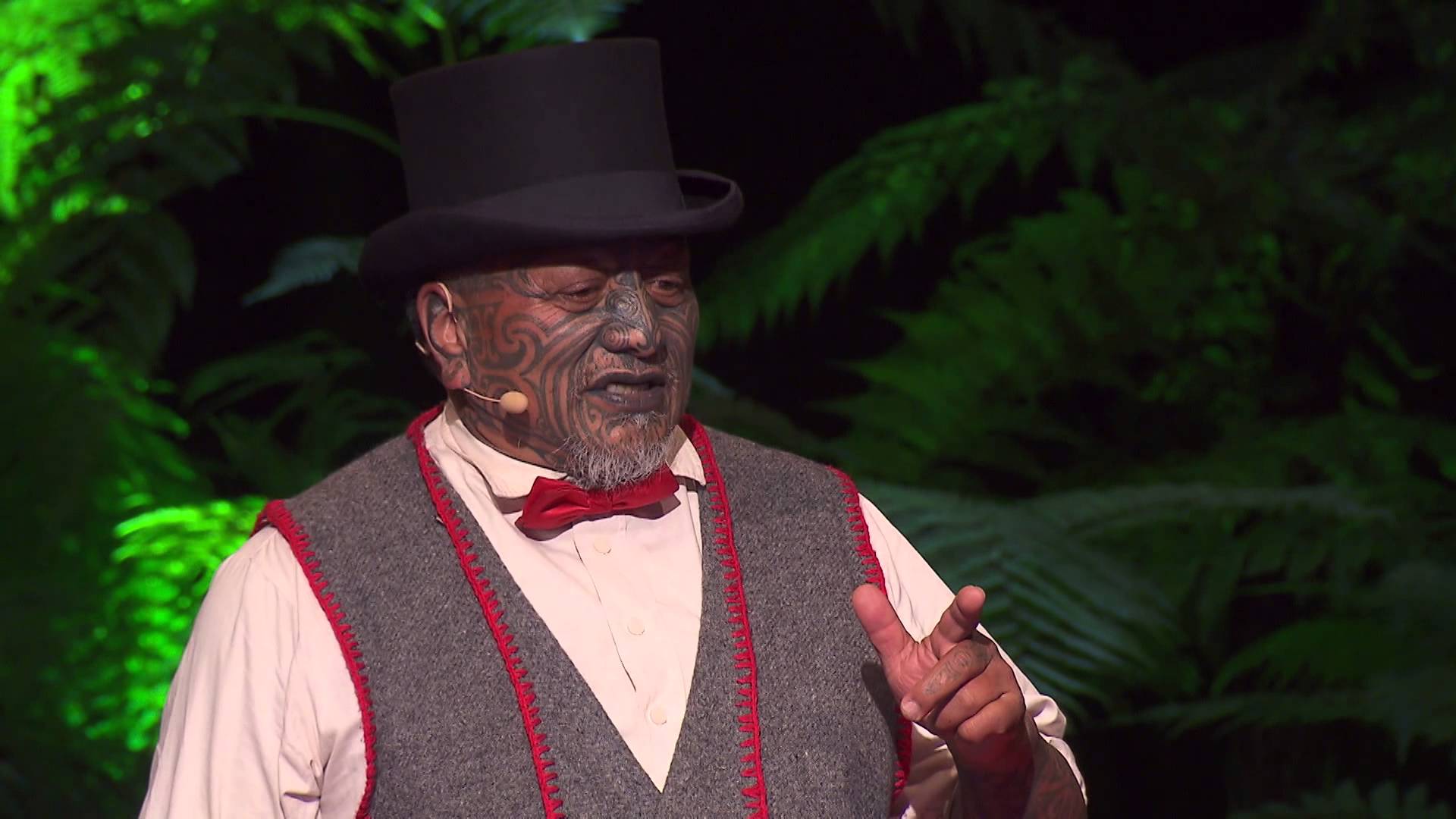

Dame Iritana Tawhiwhirangi

Welcome to TIKI STARS, a special feature that acknowledges and pays tribute to our kaumatua both past and present.

These leaders come from all walks of life and from all parts of Polynesia, Micronesia and Melanesian society. Many have distinguished political careers and many have had successful business careers. Others will be remembered for their sporting achievements and some are loved for bringing about positive change to their communities.

Our first TIKI STAR is a woman I had the great pleasure in meeting for the first time in January 2013 at the Maori National Golf Championships in Taupo. Dame Iritana Tawhiwhirangi, or Auntie E to her fellow golfers, is one of those rare individuals blessed with many talents but none more important than her “can do attitude” Her drive and leadership has transformed the New Zealand landscape forever and given her beloved people the most precious of all treasures, their language.

Dame Iritana Tawhiwhirangi

Born in Hicks Bay and educated at Hukarere Girls Collage in Hastings she worked with the Department of Maori Affairs from 1972 till 1989. She is a life member of the Maori Women’s Welfare League and Kaupapa Maori Matauranga – Maori Education Trust and is on the Board of Trustees of the Kohanga Reo National Trust.

Prominent in the kohanga reo movement she was involved in reversing the decline of the Maori language. The first Maori woman to be appointed as a district officer with the Department of Maori Affairs and became general manager of the Te Kohanga Reo National Trust Board in 1982. She is a recognized New Zealand leader for her work with the Kohanga Reo movement. “I believe that true leadership is one that exists within each individual. It is when each individual stands proudly and are able to manipulate the world around them, that is true leadership.

The first Kohanga Reo was opened in Wellington in 1982, with another 100 following in the first year. She became a Dame for all her work with the Kohanga Reo movement. Initially declining the award she then accepted the honour on behalf of all the people involved.

“I think that this award is a tribute to the families that have taken responsibility for kohanga reo over the past 25 years,” said Dame Iritana. But it is her more than 60 years’ involvement with Maori education which began at the Tikitiki School on the East Coast in 1948 and the rise of kohanga reo that secured her the title. Dame Iritana credits many others including activists Hana Jackson, Ripeka Evans, Donna Awatere and Dun Mihaka for bringing the issue to the nation’s consciousness.”It’s really a pity that only one person can receive this award.”

There were a lot of people who were focusing on the language but it just needed a critical mass – that critical mass were the children, the teachers and the wider whanau.” The idea worked and by the end of 1982 there were 100 kohanga reo around the country. By 1994 there were 800 kohanga reo – most of which operated with little financial assistance from the Government. Internationally, the model is now seen as a benchmark for the revitalisation of indigenous languages.

Despite her many years of helping others, Dame Iritana has never been “wedded to the idea” of taking responsibility for the wellbeing of people. Her philosophy is one of self-help, with a little guidance, for the best results.

The following is a transcript of a speech Dame Iritana presented to: THE 10TH ANNUAL WAITANGI RUA RAUTAU LECTURES TE HERENGA WAKA MARAE ON THE 3rd FEBRUARY 2013.

TOPIC:-

“From 1900 to now- the evolution of the Maori community.”

Tena tatau,

Tuatahi e tautoko ana nga mihi, nga whakaaro hoki i horahia i runga i te marae i te rangi nei.

Tuarua tenei te mihi ki te Kaunihera Maori me nga Wharewananga o Wikitoria raua ko Massey..kia ora rawatu koutou

When I was invited to participate in this forum to comment on the above topic I realised just how many of the last 100 years of the second century I had experienced. Short of the first twenty-nine I was around for the rest of that century.

I am fortunate to have lived for so long as this length of time has contributed to lifelong experiences and the privilege of associating with many visionaries including the “giants” of Maoridom.

I intend commenting on the period concerned and my observation of its impact on Maori development and indeed the Treaty. Others and many of you here today, have delved more deeply into the Treaty than I have so my views are very much from a personal perspective.

Given that I was not born until 1929 my recollection of the first ten years stem from all that I heard from my extended whanau and Hapu members. At that time my Tuwhakairiora Hapu, at Hicks Bay in Ngatiporou, was emerging from the 1930s depression. Survival depended almost entirely on the resources of the sea, land and forests which the Hapu had dominion over at the time. It was these resources that were the ‘riches” that mattered and that provided for our wellbeing.

In that regard there was not the dependency on Government to the extent that prevails today. There was, instead, an obligation for the extended whanau, Hapu and Iwi to care for everyone and to share available resources. I knew that my family was poor in financial terms but we were not poverty stricken.

In other words such cultural factors as aroha, whanaungatanga and manaaki were a given, and were the values (tikanga) that sustained our whanau and Hapu. On another front there was no angst over Te Reo Maori simply because it was deeply embedded in the Hapu. I cannot remember concerns over the Treaty of Waitangi being aired at all and I have often wondered about the seeming lack of debate around it.

Some of the reasons, from my point of view, could be that we did not have our land confiscated, our language was not threatened, our marae were the “wananga”, and Sir Apirana Ngata was the “demi-god” of Ngatiporou.

He, not Government Agencies, called the tune for Ngatiporou wellbeing which engendered a sense of security and purpose for our Hapu. I have no doubt that this was the case for all Hapu within Ngatiporou. His benign leadership worked. An illustration of his influence left an indelible imprint on my mind.

In 1940, “Api” as he was fondly known, visited our marae in Hicks Bay along with the Minister of Education and officials. I was eleven years old at the time and as was the custom the whole of the Hapu attended the Hui including the schoolchildren. I raise this because, in my view, it had ramifications for what happened in Maoridom some twenty years later in respect of Te Reo Maori and the subsequent importance of the Treaty of Waitangi.

In addressing the Government contingent Api exhorted them to teach us the English language… His actual words to the officials were, “I want you to teach English, English and more English to Maori children.’’

I have often pondered on what happened in Hicks Bay as an outcome of that directive and I later believed that the strapping in schools, in order to eradicate Te Reo Maori (Maori language), related, in large measure to Api’s call. He was a man of significant mana and influence in the eyes of both Government and Maori.

It transpired that the Officials took his message seriously and the strapping of Maori children for speaking their own language at school became an entrenched Education policy. We are all aware of this…it is not new to us but, as mentioned earlier, I raise it because of the Reo protests that emerged in later years.

While strapping did not occur at our school there was an outcome of Api’s statement that related to the Pakeke (Elders) of the Hapu. Such was their faith in Api that they took his message to heart and attempted to speak English. The upshot was ‘’broom the floor”, “key the door” examples.

I have deliberately cited this to get a perspective on Te Reo developments and the protests that eventuated in the sixties when Ngatamatoa emerged. I need to return to the 40s….there was an emphasis on education for us and Api pushed this to the hilt. The Maori Boarding schools (Te Aute College; Hukarere; St Stephens; Queen Victoria; Turakina and Te Waipounamu ) featured strongly and the availability of Government scholarships enabled many of us to attend. The graduates of these Colleges have made an incredible contribution to both Maoridom and the nation In this light it poses the question about the development of current education policies in a mainstream framework.

The 1940s/ 1950s decade was the period of the 2nd World War and the voluntary enrolment of so many young Iwi men took its toll on Maori developments at that time. The first half of the 50s decade was mainly wrapped around the war effort. This lasted to 1945 when the war in Europe ended. The recovery from the war years, the return of the Maori Battalion and the significant role that Maori Army Officers played in the latter half of the 1940s resulted in a range of developments affecting Maori developments over the ensuing years.

The Department of Maori Affairs harnessed the leadership potential of the Battalion officers, some of whom were Sir James Henare; Peter Awatere; and Monte Wikiriwhi. They became the forerunners of the Maori Welfare Officers regime under the stewardship of Rangi Royal who was the first Controller of Maori Development within the Department. Underpinning their roles was the Department’s 1945 Maori Social and Economic Development Act.

These leaders were held in high esteem and in my opinion laid the foundation for the importance and validity of Maori culture in the future development of the country…and I might add, in the context of the Treaty of Waitangi.

At that same time the native speaker Elders in their Iwi regions were becoming increasingly concerned about the seeming decline of the importance of the Maori language but they did not have the political savvy to deal with Government in this regard…

In the case of Pine Taiapa, a noted Maori carver, as well as being a language expert, he had got to the point of believing that the value of the language was on the verge of being lost altogether. He stated, on his death bed, that in such an event the culture would die as well

Up until the 1960s the majority of Maori were still tribally based, however a couple of things happened that were to radically change the world of Maori. First of all there were many Rangatahi (Maori youth) accessing university and assessing the impact of policies on their people. Greater attention was being paid to the Treaty and Ngatamatoa became a challenging voice on the lack of importance of Te Reo in the Department of Education. People like Dun Mihaka, Donna Awatere, Ripeka Evans, Sid and Hana Jackson and Hone Harawira were some of the forceful agents of challenge and protest that emerged.

Suddenly the Treaty became the flagship of protest in respect of language but as we now know the protests moved subsequently to address land confiscations ,seashore interests, water, spectrum ,employment, education, discrimination and so the list .goes on. The long suffering of the Elders of the past decades was able to be dealt with under the Treaty principles and by a Maori “intelligentsia’’ that was focused, again as I see it, on a true partnership that incorporated fairness and justice. Two stand out Maori organizations that must be acknowledged are the NZ Maori Council and the Maori Women’s Welfare League. They unquestionably led the way on Maori developments over several decades prior to the reaffirmation of Iwi in 1984.

Their contribution to Maori developments continues to this day. The Council’s uncompromising and unrelenting stance on the rights of Maori is well known and applauded. Secondly, the sixties began the depletion of iwi populations. The Department of Maori Affairs relocation policy moved numbers of Maori families to the cities in order for them to access better housing, employment, education and health benefits. It is now clear that we have a dual problem….urban problems on the one hand and languishing iwi regions on the other.

In the seventies and eighties there were promising developments that addressed the importance of culture and the strengths of Maori. Dame Whina Cooper’s 1975 Land March protest added to the questioning of the Treaty.

The Department of Maori Affairs 1977 Tu Tangata policy was rolled out and got immediate traction. Essentially it declared war on the constant focus on Maori problems and instead highlighted the strengths of the people

Additionally it provided opportunity for groups with a common interest to take responsibility for managing their initiatives.

Small “seeding’ grants were available to get them started but the continued viability rested with the group.

This policy was designed by Maori in the Department to move groups from depending on the Government alone. Thousands of TT initiatives were in place in the early years relating to language, sport, tribal youth activities, kokiri centers. By 1980, 81, and 82 there were many more developments and the Te Kohanga Reo policy was one. Maatua Whangai and the Nga Kaiwhakapumau Language Entity were others. Puao Te Atatu was another that was initiated by a group including Neville Baker and Donna Hall.

There are hordes of initiatives across the country, established by both Maori and Government that have underpinned Maori development over the years. In this light we should be asking, why are we featuring yet again in these problem areas and why so much investment of time and effort does not seem to curb the frightening statistics about us? As I mentioned at the beginning of this address the lack of Government resources and intervention in the early stages of the 1900s meant that there was no other entity except the extended whanau within the Hapu to support the collective needs of everyone..

The assumption that Government has the answers is now under scrutiny and the Treaty features in questioning the policies and practices that are rolled out to ‘fix’ our lives. The extended whanau is marginalized and to our detriment we have allowed this to happen…even more fearful is that we have fallen into the trap of believing the money alone will overcome all adversities.

When we had meager funds we survived. This is not to undervalue funding but rather to question whether such resource is enabling people to grow in dignity, purpose, responsibility and hope or whether we pursue policies that are disregarding our culture. Are we talking about culture in a Maori specific context where the extended whanau is the key or are we continuing to condone the ‘FIX IT’ mentality that subjects whanau to well meaning services only?

I am a staunch supporter of the Whanau Ora policy as its focus is on the dignity and potential of each whanau, within the bosom of its extended whanau, Hapu and Iwi. It aims to return us to the cultural practices that prevailed at the beginning of the 1900s. We have gone full circle in addressing Maori developments. Whanau Ora takes us back to what worked without reliance solely on Government.

In conclusion I want to refer to Thomas Jefferson who said:-“ I know of no safe depository of the ultimate power of the society but the people themselves and if we think them not enlightened enough to exercise their control with a wholesome discretion, the remedy is not to take it from them, but to inform their discretion.”

Right now I believe that the Whanau Ora Kaupapa embodies that statement in its entirety and my crystal ball says it’s going to gather Maori development momentum. In simple terms…..the real strength of Aotearoa resides in the strength of its extended whanau/families….knowing this is one thing, harnessing it is another!

Kaati ra e hika ma, ko oku whakaaro anake enei.

Nga mihi nui I roto I te wawata kia piki te ora o nga whanau katoa a taihoa nei.

Tena tatau katoa.

Iritana….3 February, 2013